Jerald

Broken necks, peacocks and rice bowl pedals.

Written by Elisa Chan | Photography by Phua Li Ling

We walk round to the back of the house, and are met by a tiny woodworking shed.

It has grey paneled walls, a sloping black roof and a small window that “does not open”, Jerald informs me apologetically as I tap at it hopefully. The poor ventilation means that he usually avoids the heat of the day and comes out here at night to work, guided by the light of a torch.

Of course, internal shed temperatures could not bother me less. I am thrilled to find myself in a quaint workshop that looks like it might have belonged to Santa and his elves. Except that, instead of a magical creature in a felt hat, it’s Jerald the luthier in a SpongeBob shirt and flip-flops, cheerfully feeding some wood through a scroll saw.

We are introduced to some of his tools. Powerful machines which slice and grate with loud mechanical shudderings, but also dainty gadgets that fit in your hand like sweet vintage toys.

I slip my finger into an Ibex carving plane—a golden shoe for a finger puppet!—and slide it across a block of wood to see what it does. Jerald watches me as I push it around ineffectively for a while. I finally find the right pressure and angle, and the whisper of resistance under my fingers tells me that I have shaved off the thinnest sliver of wood. Jerald notices the look of satisfaction on my face, and smiles.

“There, you’ve found it!”

The workshop is strikingly neat; overturning all my baseless presumptions that workshops are cluttered, chaotic spaces. “It’s like this all the time?” I ask suspiciously. “Yes, I didn’t tidy up for you guys,” Jerald laughs.

This is perhaps all the more remarkable considering the fact that Jerald is clearly no minimalist when it comes to tools.

“My mentor will tell me: you only need one fret file! And that works for him. But that’s really not me. I like trying new tools, and seeing how they are different from each other. Maybe I can do a better job with a different tool.”

As Jerald bounces around his workshop expounding on fret files and “the best oil” (Kroil, FYI) and how adding baking soda to super glue makes the glue even more super, it occurs to me that we are in the presence of a true-blue geek.

I don’t know if all luthiers are geeks. But I can tell that Jerald loves the nuts and bolts of his craft, and this, combined with his genuine infatuation with guitars, seems to produce a level of work that goes beyond skin-deep.

His workmanship appears to stand up to all kinds of tests—even violent ones.

“I once repaired a broken guitar neck. Then it got broken again, but not at the same place! And I told my client: you see, it didn’t break at my repair.

“The fixed part can actually be stronger than before.” Jerald laughs at the disbelief on our faces. “I have my secret methods.”

While Jerald demonstrates how he hand-drills a perfect 90-degree hole into a piece of wood using a metal guide, Li Ling lingers outside the workshop window with her camera, peering in at us like we’re a couple of kids messing around in a playhouse.

I’m enjoying a delightful sense of surreality… which only increases when I discover the peacocks.

As it turns out, Jerald’s Santa hut is hardly the strangest thing in this neighbourhood. We’d been too distracted by all this woodworking business to notice that the shed sits right next to his neighbour’s two-storey aviary.

For several minutes, Li Ling and I gape at the half dozen peacocks ambling about in their caged enclosure. The neighbour, possibly encouraged by the presence of Li Ling’s camera, undertakes a feeding of the birds, which generates a flurry of exotic bird action and accompanying noises.

Jerald takes a moment to commune with his “favourite bird friend”, a spritely-looking turaco with jade green feathers and piercing red eyes which has flown up to the fence to say hello. I am unsurprised that Jerald has a “favourite bird friend”. He’s a personable guy.

He later tells me that the avian cacophony outside his bedroom window wakes him up at dawn. This, then, is the unspoken give-and-take exchange between neighbours: drilling noises at night for bird squawks in the morning.

Jerald has brought us upstairs and we are hanging out in his bedroom like teenagers, looking at his stuff. He fishes out his very first guitar. It is a cheap one which his father bought for him when he was thirteen years old, thinking that all this would just be “a passing phase”.

I’m looking at the Ghostbuster stickers and white-ink cartoon drawings scattered across the surface, and thinking: charting the course of Jerald’s relationship with guitars is going to be challenging. It’s like excavating the root ball of an old tree—it goes deep and it grows dense. The stories spiral from all directions.

But at least, there’s a clear orientation towards a particular center.

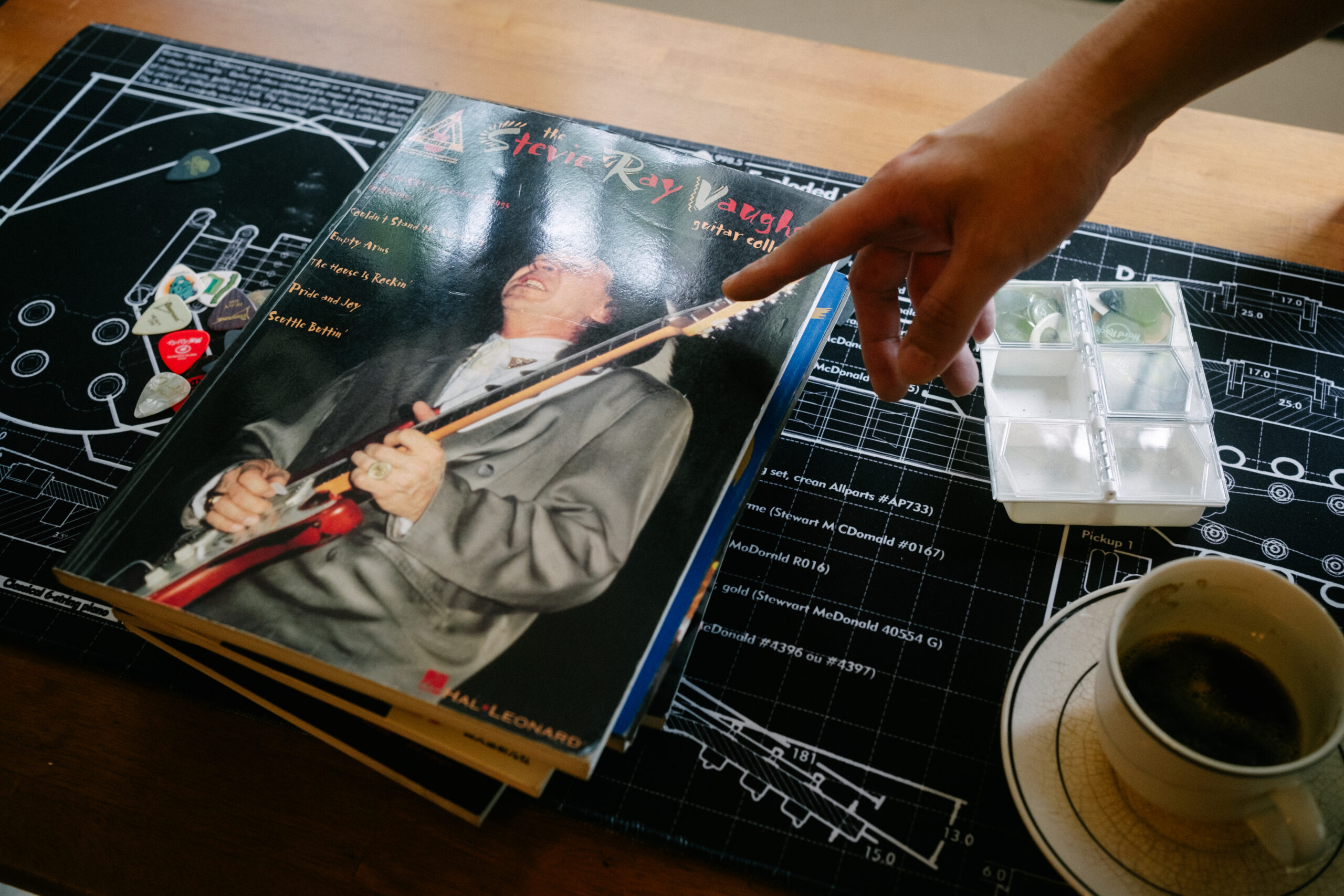

“I used to go to this music shop in Ang Mo Kio when I was a teenager, and one day I bought a CD just because the cover had a picture of a cool guitarist on it.” Jerald lays a tab book on the table, and we examine the cool guitarist. Stevie Ray Vaughan is sporting an eighties-appropriate baggy blazer, a black hat, and impressively large gold rings.

“And then when I went home and heard the music, I was blown away and bought this book at Yamaha and learned all the songs.”

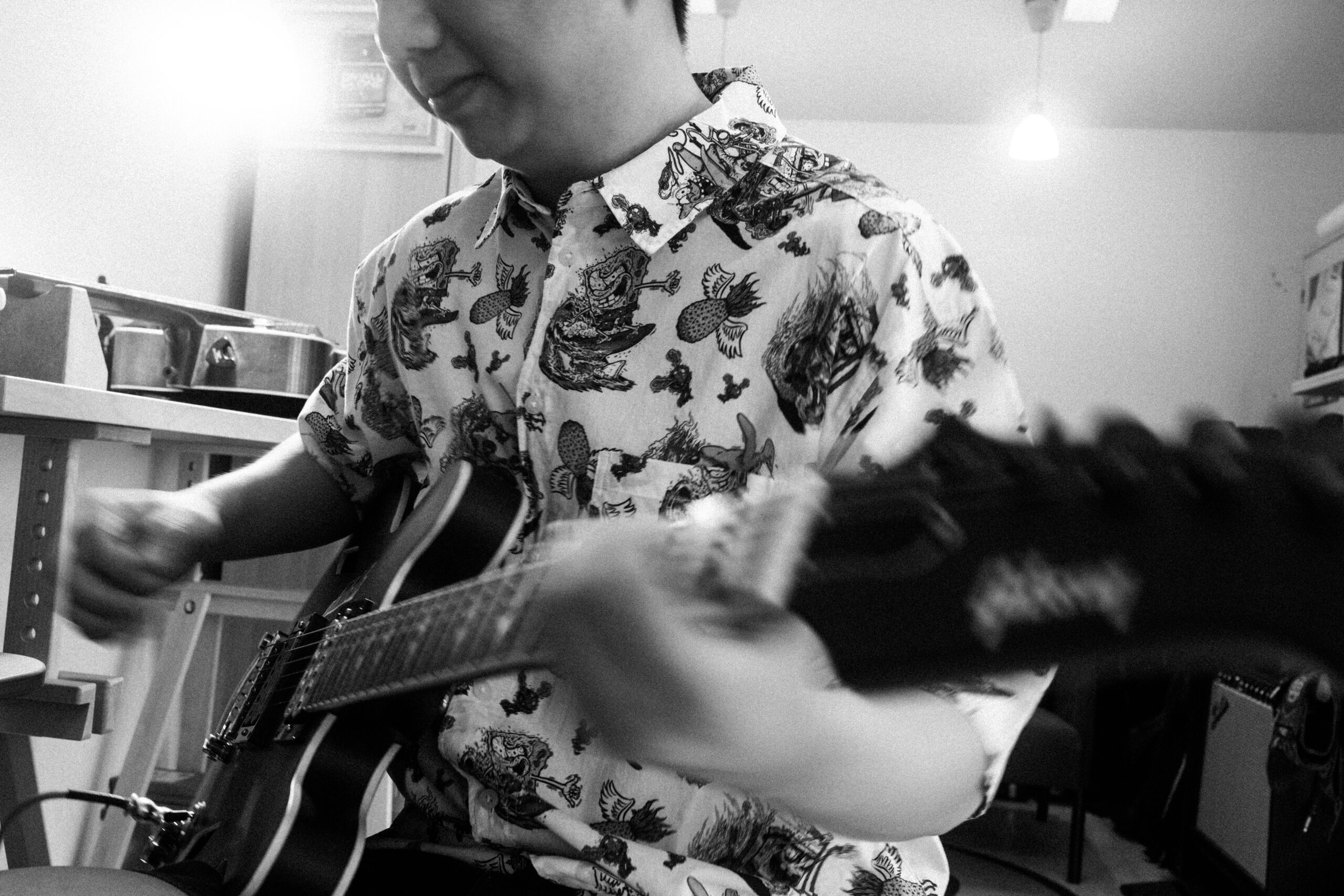

When Jerald says he learned all the songs, I take him at his word. He was the kid who would play guitar for hours after school, have dinner, and then play guitar again for hours after that. He joined bands and formed bands when he was in secondary school; he participated in talent shows. He studied music production while in polytechnic. He wanted to be a guitarist.

And then, of course, he ended up working in a bank.

Jerald speaks quietly: “I really wanted to be fair to my parents, in a way. I had the privilege of reaching this point, thanks to them, and I felt like this was the right thing to do.”

But he worked that corporate job for only a couple of years, on a training contract. “And then on the day that my ‘real’ bank job was supposed to begin, I couldn’t go. I’d signed the contract already, but I just couldn’t.”

Instead, he returned to that one central thing: he started knocking on doors and asking every music store if he could work as an apprentice. “If I can’t be a guitarist, I want to serve guitarists.” Jerald smiles.

Eventually, he found work at one of the shops.

“Then one day this Italian guy came into the shop, and he watched me for a while. I didn’t know he was a master luthier. He told me later that he could tell that I really wanted to do this—that I was serious. So he offered to teach me the craft, and he became my mentor.”

What was clear to his mentor then (and clear to everybody who hangs out with Jerald for ten minutes) is that Jerald is one heck of a determined guy. You see the evidence everywhere.

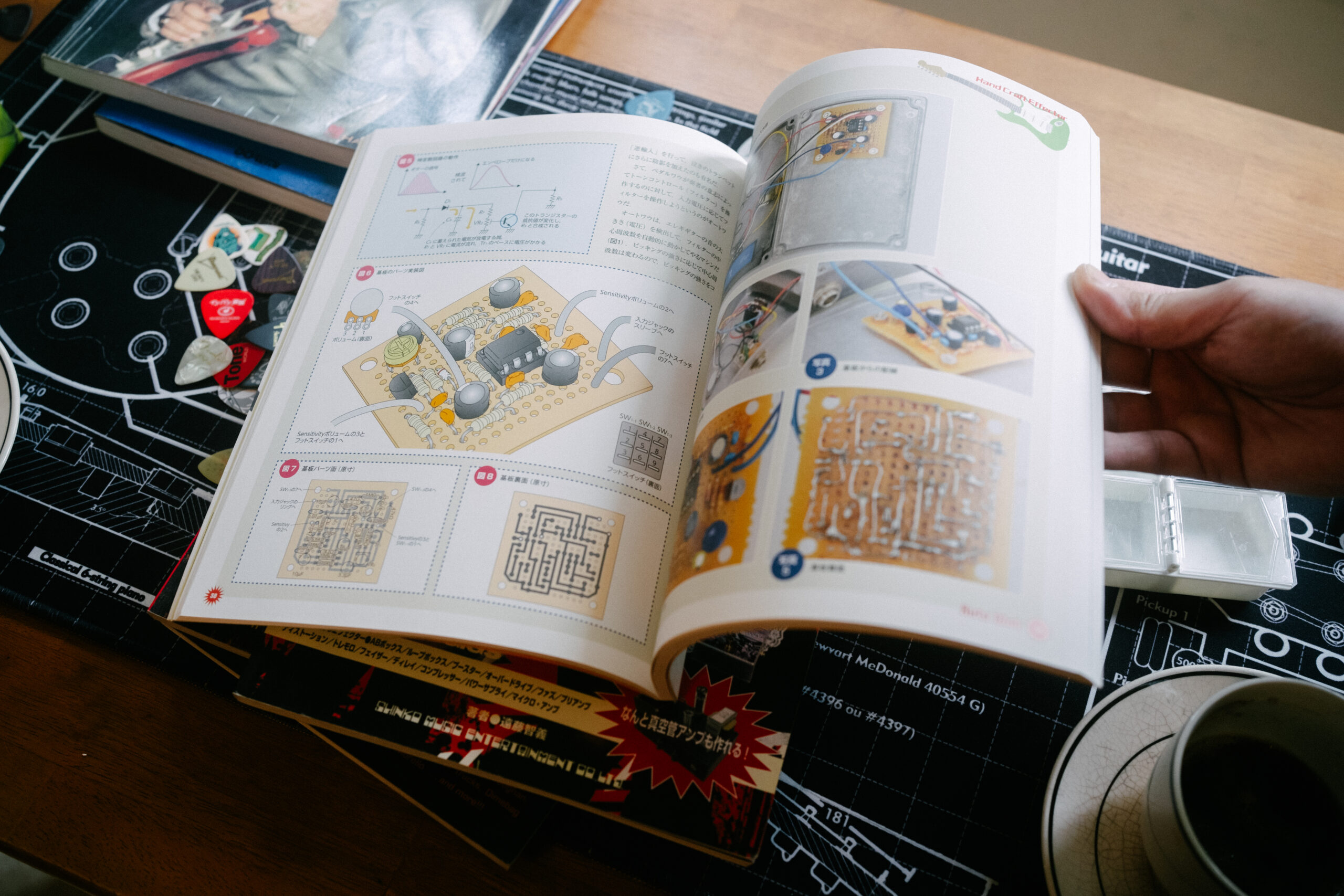

We are looking at an old Japanese guitar pedal book.

It is covered in diagrams and all manner of electronic gibberish, made none the clearer by the Japanese characters accompanying it. “I couldn’t read it at all, but I would look at the pictures, and try to figure it out that way.”

This is, in fact, the first time that I’ve paid any attention to a guitar pedal, let alone examined its incomprehensible innards.

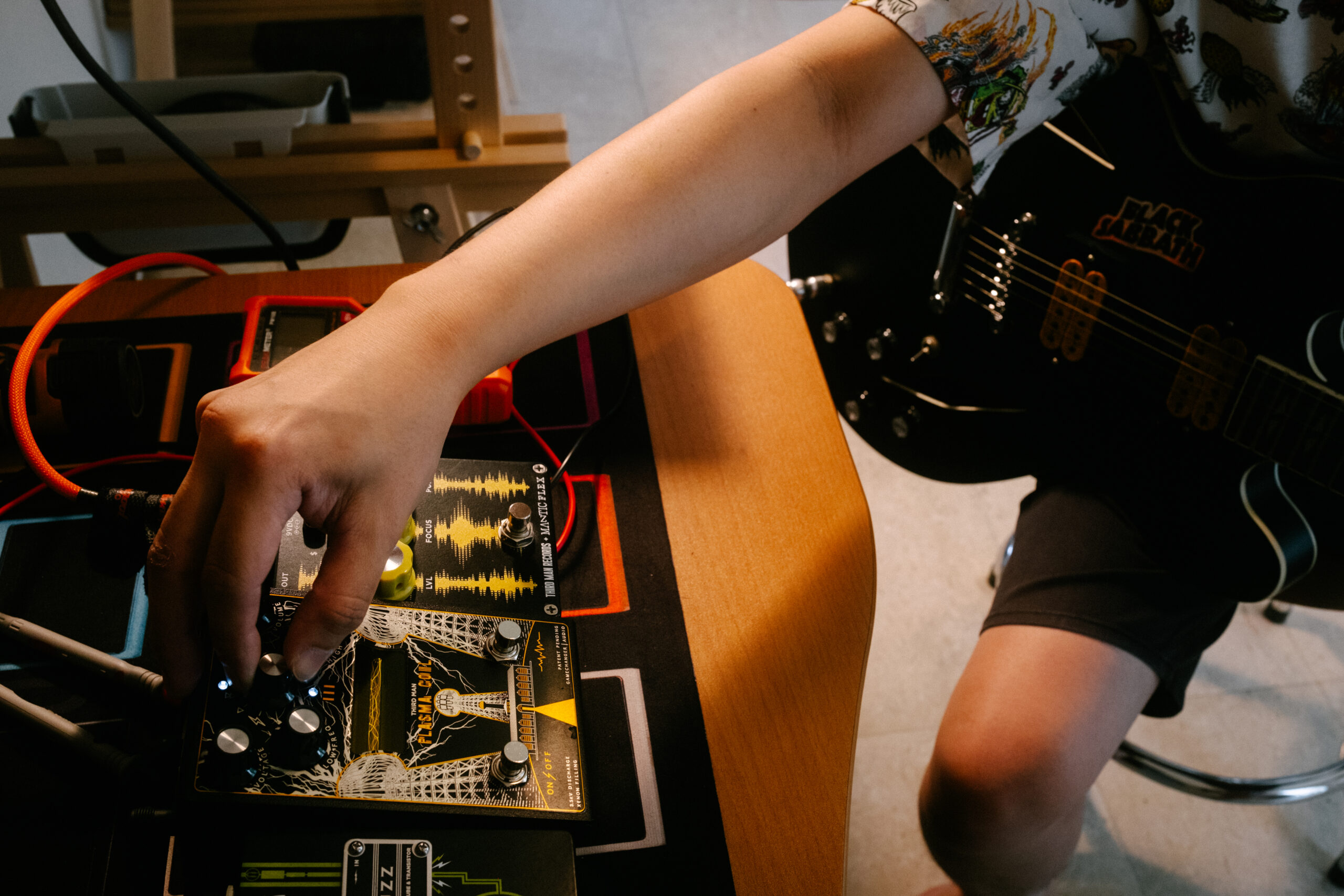

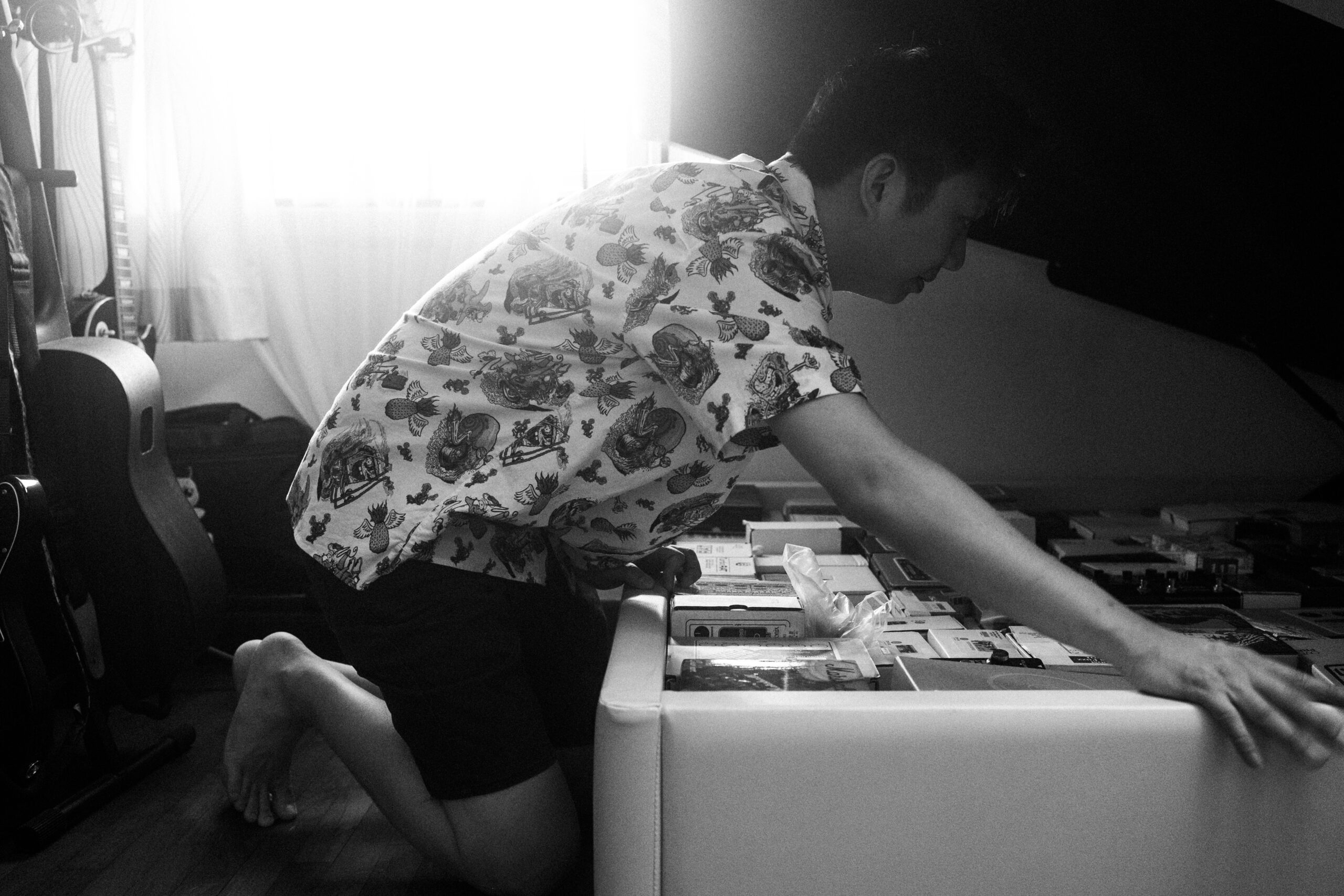

As it turns out, I will become acquainted with a plethora of pedals today, most of which are neatly stored under Jerald’s bed—a fact revealed with dramatic flair when he suddenly heaves up his mattress without warning, causing me to yelp in surprise.

“I couldn’t just keep buying guitars when I was younger. My parents wouldn’t have allowed it, and I didn’t have that much money anyway. So, I bought pedals instead. You can hide a pedal!”

I ask him what he finds interesting about pedals.

Jerald quickly demonstrates their different sound effects, but this really isn’t the point. “I think one of the reasons why I love collecting them is that some of the older pedals contain chips or parts which are just not manufactured anymore.” Technology has moved on, and Jerald is safeguarding what has fallen by the wayside.

What he neglects to mention is that these pedals in his collection are beautiful to look at. They are quirky, and have distinct personalities. Li Ling smiles as she turns over a Korean pedal which is made out of two stainless steel rice bowls sealed together. One Russian pedal comes in a wooden box that looks like it might contain a bomb. Another has a dancing electric spark that you can view through a little window.

“I like that one because it reminds me of the Ghostbusters trap,” Jerald says. We’ve come to realise that he’s not just a guitar geek.

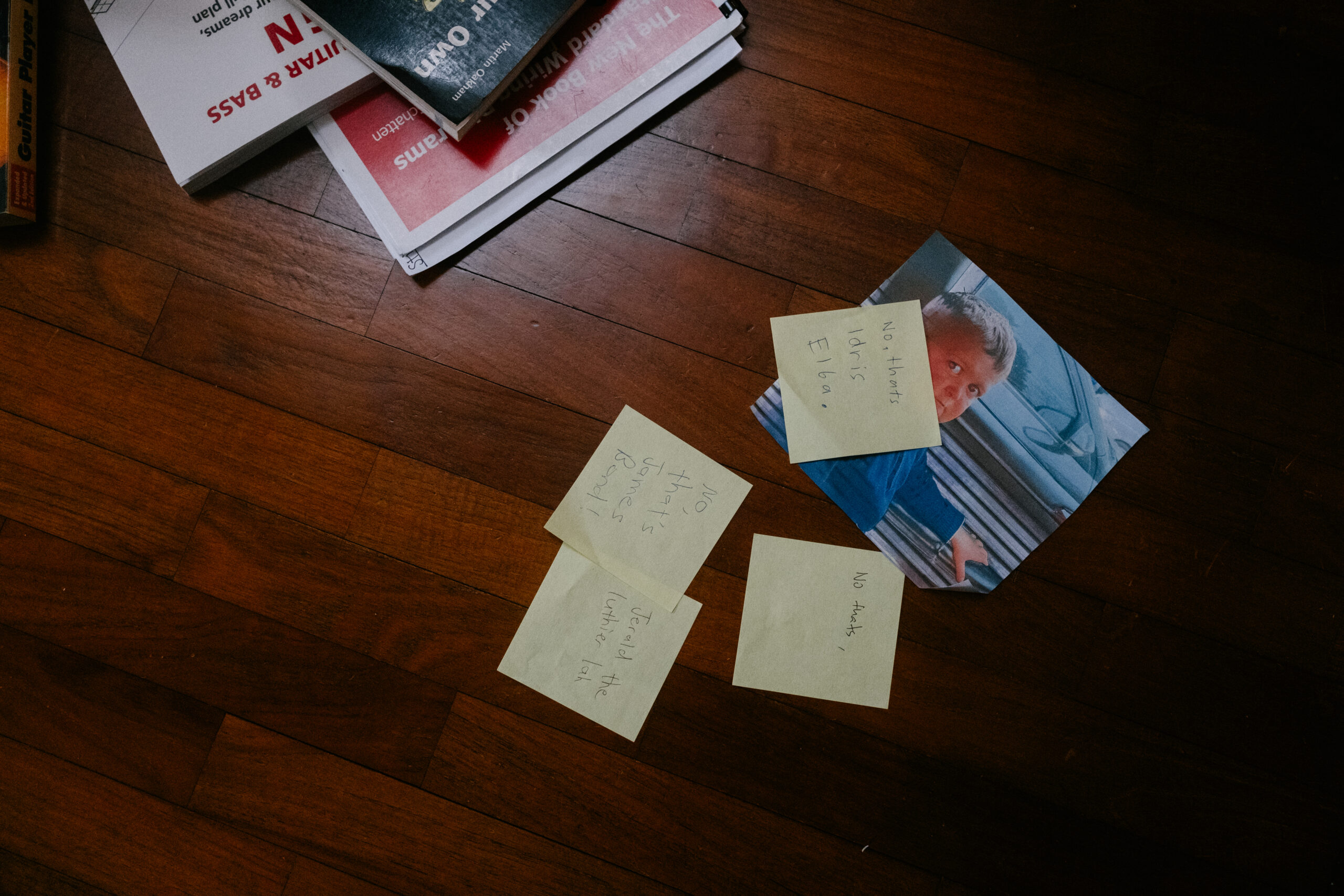

Throughout our meeting, Jerald has self-deprecatingly referred to his “hoarding” tendencies, but that doesn’t feel like the right word to use. Yes; he has many things. He collects pedals, and guitars, and guitar picks. He hangs on to old magazines and books and DIY blueprints even though he’s outgrown them.

But this is not a haphazard blur of possessions. There is a thoughtfulness and elegance to all of this collecting and keeping.

He knows where everything is, and what everything is.

These objects are like tangible filaments of memory and story; they are numerous, but I can tell that they are oriented to a particular center. Sometimes, volume doesn’t dilute meaning, but condenses it.

I am no collector myself, but I can’t help but respect this; even admire it.

There is no clutter here, and no chaos. Everything is where it should be.

Find Jerald on Instagram at @guitar.fix