David L

Major scales, cheeky pipes and iron filing sketchbooks.

Written by Elisa Chan | Photography by Phua Li Ling

“I’m a little obsessed, honestly,” David confesses, as he shows us his small collection of trumpets.

I hold one nervously—a Martin Committee from 1940-1942. It feels a little heavy in my unpractised hand, but balances nicely. There is a charming whiff of steampunk about it, as if someone had taken parts from an old-timey train and reassembled them into a nifty little package of brassy tubes and levers.

I press down on the keys, and they surprise me with their mechanical smoothness.

David hands Li Ling a trumpet too, and we suddenly find ourselves in an unlikely Trumpeting Circle. A discordant sound-soup of honks and squawks begins to bubble up and fill the small bedroom we are in—the room which David informs us was carefully chosen for being “furthest from the neighbours”.

I squelch my schoolgirl giggles at our cacophony of rude noises, and focus on finding that elusive C. Once or twice, a pure tone makes it through, like a voice breaking. It sounds sweet, dark, and utterly open; a siren song over water. I am starting to see how the trumpet obsession takes hold.

“My trumpet instructor is rather philosophical. He will say things like: ‘the trumpet is just an amplifier of what you’re doing with your body and mind’.

“Or: ‘be aware of everything just before you play—like how your lips are feeling, what your body is doing—and then forget all of it when you begin.’”

Ah, the paradoxical dilemma of having to be intentional about what you’re doing…but also not pay too much attention once you get going! A treacherous mental game attending any activity requiring muscle memory.

This final nugget of Trumpeting Wisdom takes me a moment to digest, but I think I understand what David means. He’s referring to the temptation to get distracted or carried away at precisely the moment when calm focus is needed. So often, the art that succeeds in cracking our hearts wide open is built on something that looks a lot more prosaic: a foundational base of disciplined technique that’s been carefully nurtured over hours and hours of practice.

Li Ling and I are now sitting at David’s dining table, where he usually draws. The light from the opposite window hits the table at just the right angle, for his dominant left hand.

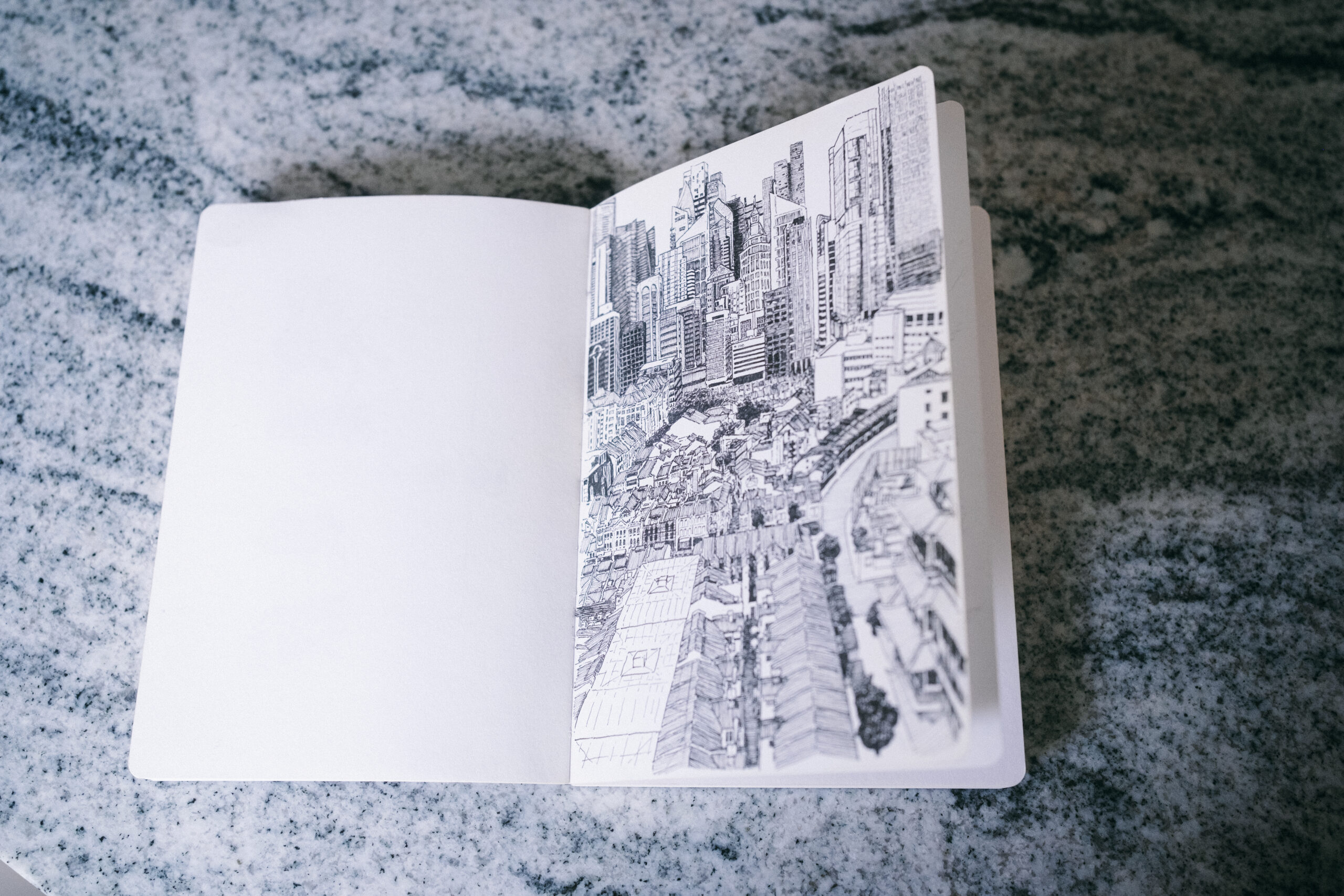

A drawing of the shopfront of Silver Kris Comics—an old comic book shop in Marine Parade market—features the tiniest of tiniest comic book covers, all uniquely drawn. “I know I don’t really have to do that, but I can’t help it,” David laughs.

It so happens that his early love for comics has greatly influenced his work; you can see hints of this in the hatching strokes that he uses to create contour, and other visual tricks he employs. “This white outline here, I did it without really knowing why, but it worked to separate the object from the background. And then I realised that it was a comics thing.”

These are the littlest of details that David is drawing our attention to, like a nature guide pointing out tiny camouflaged creatures hiding in the foliage—clever techniques and tricks that Li Ling and I would never have noticed, left to our own devices. Meanwhile, I find myself especially struck by a particular detail myself: his long straight lines, all drawn freehand and comprising shorter strokes which almost connect, but don’t. They look impossibly straight to my eye, but also unmistakeably human.

“I don’t like my drawings to look architectural. I want something…more handmade.” David points to a small section of pipe in a construction scene. “That’s obviously not exactly straight, or correct.”

He’s right, that pipe isn’t any kind of pipe you’d find in the real world. It’s a little bit cheeky.

We flip through the pages of an older sketchbook, and find several drawings of bus interiors. The passengers are different each time as he’s sketching real-life moments, but the scenes and perspectives remain largely the same.

“Sometimes, I’ll draw the same thing a few times over because I’m learning the vocabulary. Now I know how to draw a handle on a bus!”

I like this idea of image vocabulary; a good reminder that so many big things are made up of little things. No music without notes, no prose without words, no bus interiors without bus handles.

Also, no mastery without practice. I’m looking at that stack of sketchbooks—one of which is shedding its cover ferociously and leaving black splinters across the table—and I am flabbergasted by the millions of pen strokes they must collectively hold, like boxes containing iron filings carefully pulled in all directions. David is clearly someone who appreciates the reward of the long route, versus the short-cut.

“It’s like, with the trumpet, I know I have to fix problems slowly and a step at a time, and make myself sit down and practise a single note ad nauseum until I get the muscle memory.

“I can only play five good notes, but when I play them, I get actual chills from the tone, the optimal way my body is working, and the way I’m thinking about those notes.”

I ask David what he enjoys about drawing, exactly? He says that there are a few stages he especially likes: the beginning—when he gets to plan the drawing, and the middle—when things start to take shape and he’s in the flow of it, but not yet worried about the final result.

“Also, I like having to have faith in my own abilities. Sometimes when I’m midway through a piece, it can look terrible and not at all like what it’s supposed to look like. But I’ve learned to just power on and trust in the process; believe I planned well, and that the strokes are the way I intend them to be. I really enjoy that sort of confidence in myself.”

We are reaching the end of our meeting and Li Ling invites David to sit on a chair in the middle of his cavernous living room, for a photograph. His flat is minimally decorated and has a marked quietness. I can’t help but feel like I’m in a chapel or a gallery; the sort of space that seems to be waiting to hold something, only to let it all go again. David himself looks like an art installation—one unmoving figure propped up in the middle of all that negative space, and surrounded by backlight.

I’m watching them, listening to the soft clicks of Li Ling’s camera, and thinking about something else that David had said earlier:

“I was talking to a photographer friend once, and we agreed that a lot of art is just putting the right stuff into the picture. This is especially so with drawings: if something’s too boring in the frame, I leave it out. If something’s cool, I embellish it.”

Choosing what to discard, and what to treasure: a universal challenge. I wonder what’s in Li Ling’s frame, and what will be in mine.

Find David and his work on Instagram at @i_am_davo